He was born in Stilo, Calabria (Italy), in 1568. When he was a teenager, he entered the Dominican Order and developed his own philosophical culture starting with the reading of Platonists’ and Telesio’s works. In 1592, Campanella was on a first trial for heresy; then, he was on another trial in Padua and, finally, in 1596 the last trial in Rome ended with a condemnation and abjuration. In 1599, Campanella organized a conspiracy against the Spanish government to promote a political and religious reform bringing Christianity back to its roots and establishing a Republican government founded on philosophical principles. Campanella was then arrested for conspiracy and taken to Naples where he was sentenced to life imprisonment and where he remained for 27 years. In that period, he was able to write his major works, including la Monarchia di Spagna (1601), La città del sole (1602), De sensu rerum (1603)¹.

Campanella’s education on politics developed between the end of the 80s and the beginning of the 90s, a period of time during which Campanella approached the reading of some Machiavelli’s pieces such as Il Principe, i Discorsi, and probably La vita di Castruccio Castracani². According to several scholars, including Giuliano Procacci and Vittorio Frajese, numerous “Machiavelli’s re-echoes”³ characterize Campanella’s works, particularly Monarchia di Spagna as — regardless of problems of dating —conceived and written at the time of 1599 conspiracy.

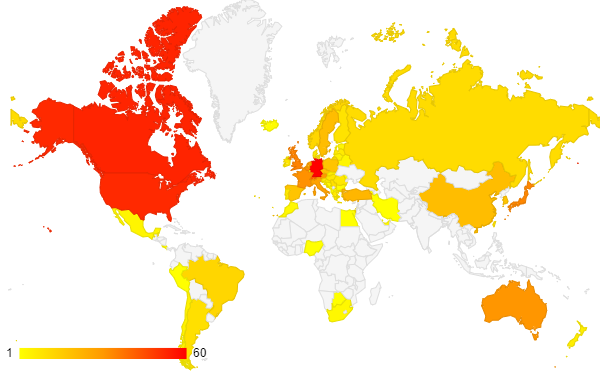

Campanella’s pieces that have been selected are mainly written in Vulgar Italian originally and, sometimes, were translated into Latin from the author himself later: la Monarchia di Spagna (1601), La città del sole (1602), la Scelta d’alcune poesie filosofiche (1622) e la Monarchia di Francia (1636). From a linguistic perspective, in Stilo philosopher, a «gradual and systematic resemantization of ethic, political and religious vocabulary can be noted, borrowed from the tradition but rendered effective within an original conceptual framework»⁴. Tommaso Campanella’s compositions have been translated into 34 languages and are spread throughout more than 60 countries in the world.

Distribution of the translations of Tommaso Campanella’s works

Bibliographic

Addante L., (2004), Campanella e Machiavelli; indagine su un caso di dissimulazione, «Studi storici», luglio-settembre, Carocci, Roma.

Campanella Tommaso, Treccani (o.l.) (last consulted on 14/10/2020).

Frajese V., (2002), Profezia e machiavellismo, Il giovane Campanella, Roma, Carocci.

Frajese V., (2014) (o.l.), Tommaso Campanella, Enciclopedia machiavelliana, Treccani. (last consulted on 14/10/2020).

Procacci G., (1995), Machiavelli nella cultura europea, Roma, Laterza, p.161.

Suggi A., (o.l.) (2009), Lessico etico-religioso e politico di Tommaso Campanella (last consulted on 14/10/2020).

Photo of Skara kommun / CC BY 2.0

¹ https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/tommaso-campanella/

² https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/tommaso-campanella_%28Enciclopedia-machiavelliana%29/

³ Procacci G., (1995), Machiavelli nella cultura europea, Roma, Laterza, p.161.

⁴ Suggi A., (o.l.) (2009) Lessico etico-religioso e politico di Tommaso Campanella