Born in 1548, in Nola, Campania (Italy), he belonged to the Bruni family. At the age of 17, he entered the convent of Saint Dominic in Naples. In 1576, when in Rome, he requested to be removed from the clerical state after being accused of heresy due to his revolutionary opinions.

He wandered in several cities — Geneva, Toulouse, Paris, London, and Frankfurt — until he was arrested by the Holy Inquisition in Venice, in 1591. During the process, he declared that he wanted to recant, but once he was in front of Roman Inquisition, during a second process, he demonstrated to hold his position and faced his death sentence at the stake that occurred in Campo de’ Fiori (Rome), in 1600. Bruno’s philosophy develops from the idea that God — unity and infinity at the same time — multiplies in infinite substances. According to Bruno, religion means recognizing God and God’s mutable forms everywhere. Despite using terms of earlier schools of thought, the originality of Bruno

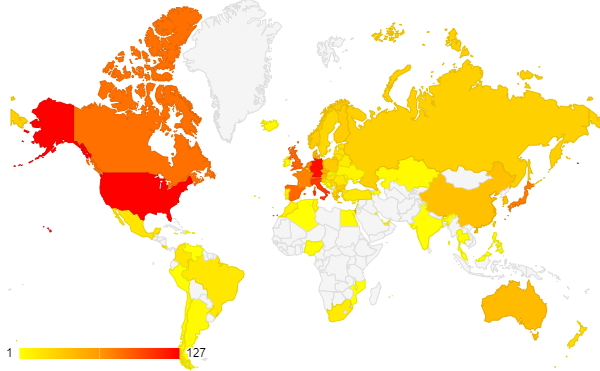

lies in the inspiration at the base of his speculations about metaphysical transvaluation and the infinity of the world that are strongly connected to morality. In fact, Bruno breaks with the determinism inherent in the circularity of one and the many, suggesting that a cognitive act is an act of freedom and means overcoming nature. This divergence is evident in the literary field too, as he is one of the first intellectuals to promote men’s and poets’ freedom, against Aristotle’s Poetics and against imitations. In fact, Bruno rejects literary genres and opposes grammarians and pedantic normativism¹. The choice of Vulgar Italian itself is intimately connected with his new philosophy; Bruno, in fact, states that he is driven «by the awareness that a new thought needs a new language»², even if this choice may be explained with his participating in London cultural clubs where vulgar language was preferred, according to some scholars such as Giovanni Aquilecchia³. The interweaving of different language registers seems to be connected to Bruno’s conception of Life-infinite matter, thus «from the point of view of reality consistency, order and beauty, everything has equal value and dignity»⁴. The selected Bruno pieces are therefore, all those works that were written originaly in Vulgar Italian: La cena de le ceneri (1584), De la causa, principio e uno (1584), De l’infinito, universo e mondi (1584), Lo spaccio de la bestia trionfante (1584), De gli eroici furori (1585), La cabala del cavallo pegaseo con l’aggiunta dell’asino cillenico (1585) and il Candelaio (1582). The translations of said works are in 30 languages and are spread throughout 90 countries in the world.

Distribution of the translations of Giordano Bruno’s works

Bibliographic

Aquilecchia G., (1953), L’adozione del volgare nei dialoghi londinesi di Giordano Bruno, «Cultura Neolatina», XIII, pp. 165-189.

Bruno G., (1994), Spaccio de la bestia trionfante, prefazione di Sturlese R., Istituto Suor Orsola di Benincasa, Napoli.

Bruno Giordano, Treccani (o.l.) (last consulted on the 6th of October 2020).

Campa R., (2019), Il convivio linguistico. Riflessioni sul ruolo dell’italiano nel mondo contemporaneo, Carocci, Roma.

Ciliberto M., (2005), Pensare per contrari. Disincanto e utopia nel Rinascimento, Roma, Edizioni di Storia e letteratura, p. 219.

Photo of Dorli Photography / CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

¹ Ciliberto M., (2005), Pensare per contrari. Disincanto e utopia nel Rinascimento, Roma, Edizioni di Storia e letteratura, p. 219.

² My translation. Bruno G., (1994), Spaccio de la bestia trionfante, prefazione di Sturlese R., Istituto Suor Orsola di Benincasa, Napoli.

³ Aquilecchia G., (1953), L’adozione del volgare nei dialoghi londinesi di Giordano Bruno, «Cultura Neolatina», XIII, pp. 165-189.

⁴ Ciliberto M., (2005), Pensare per contrari. Disincanto e utopia nel Rinascimento, Roma, Edizioni di Storia e letteratura, p. 219.